Memory Hoax? The Use of Hypnosis in Memory Retrieval

Students in Dr. Emily Stark’s Social Psychology course complete a research project where they identify a misconception related to psychology, conduct both background research and an empirical project measuring belief in that misconception, and summarize their findings in a short blog post paper or by creating an infographic. The goal is to build student research skills as well as showcase the importance of thinking critically about information encountered in the media or in popular culture. This post is one of the papers submitted for this project. For more information on this project, just use the contact page to contact Dr. Stark.

By Brooke Morris

The memories of our past can often be slippery and elusive. Personally, I have always struggled with my memory, whether it be where I placed my keys or important conversations with friends. Often, I will have someone relate a shared experience with me, only I will have no recollection of such an event. That is why, for me at least, it is a very appealing thought to undergo a therapy session where someone can coax some long-forgotten memory out and into the open. Hypnosis has long been thought of as the solution to fuzzy details and murky memories.

For years, people have believed that hypnosis creates a window into the mind, where a person can seize the controls of an individual’s brain. This concept has been extremely popular in the media, with big blockbusters like Now You See Me and Get Out showing hypnosis as an all-powerful tool to control a person and manipulate their mind. However, how accurate are these beliefs, and how far have they strayed from the truth?

To sort the wild misconceptions from the truth, I found a study that tested the accuracy of hypnosis in an area that matters most, eyewitness accounts of a crime. A hundred college students were shown a video of a staged crime, hypnotized, then asked to identify the thief (Sanders & Simmons, 1983). Many other factors were manipulated for the students, such as distinctive clothing worn and varying wait periods, but all came to the same conclusion. Compared to the control group, those that were hypnotized were actually less likely to identify the thief. Instead, hypnotized participants were more affected by the distinctive clothing the thief wore, allowing more wrongful identifications (Sanders & Simmons, 1983). The only advantage that hypnosis seemed to bring was added confidence in the participants' testimony. Thus, I believe that this study highlights the inaccuracies of hypnotic memory retrieval and demonstrates the consequences of undue confidence in memories.

However, while this might be a known fact in the research community, it doesn’t mean the average person is aware of it. To determine how many people fall under the sway of popular misconceptions of hypnosis, I found a representative survey of 1500 participants. This survey posed a series of statements of misconceptions surrounding hypnosis, where participants rated how believable each one was (Simons & Chabris, 2011).

Due to extensive media coverage and films surrounding hypnosis, the results were varied. A staggering 55.4% of the sample believed that “Hypnosis is a useful tool in helping witnesses accurately recall details” (Simons & Chabris, 2011). I found this percentage very revealing of public attitude, due to the nature of American courtrooms, which functions under the basis of absolute certainty when handing out convictions. However, this statement also garnered the most responses of uncertainty, showing the great degree of mystery surrounding hypnosis. With so many varying depictions of hypnosis, it is not surprising that there is a wide range of belief and certainty on the subject.

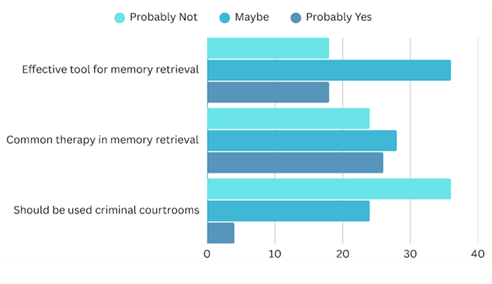

While this survey was informative, I wanted a more comprehensive understanding of what people believe hypnosis is capable of. To do this, my Social Psychology class conducted a survey on the students attending Minnesota State University. Since most of the students at college range in their twenties, I thought this could show a new generation's perspective on hypnosis.

This survey asked participants a series of questions to determine how they thought of hypnosis and its trustworthiness in memory retrieval. Interestingly, the common attitude towards hypnosis reflected that of the national survey, with general doubt of the concept. One statement did stand out to me, which declared hypnosis as a reliable tool to be used in eyewitness testimony. Participants took a firmer stance than the national survey, stating that it should probably not be used in the criminal courts. Hopefully, this might suggest that hypnosis misconceptions might have a looser hold on this generation than past ones.

Ultimately, a clear definition and function of hypnosis should be declared to the general public. Hypnosis does not allow a person to reach in and pull out a memory. As nice as it would be to remember how I know a person who clearly remembers me, it is not possible through hypnosis. It can, however, be used to treat many anxiety and stress disorders. Hypnosis involves a person becoming deeply concentrated and relaxed, generating a state of mindfulness. When supplemented to established therapies, it has been shown to reduce stress and anxiety (Hammond, 2010). By affecting physiological processes, like skin temperature and pulse rate, it can help reduce anxiety and stress (Hammond, 2010). So, while hypnosis is not as mind-bending as in the movies, it doesn’t mean it is useless. We need to understand how hypnosis actually works, and how it can truly help people.

References

Hammond, D. C. (2010). Hypnosis in the treatment of anxiety- and stress-related disorders. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics, 10(2), 263–273. https://doi.org/10.1586/ern.09.140

Sanders, G. S., & Simmons, W. L. (1983). Use of hypnosis to enhance eyewitness accuracy: Does it work? Journal of Applied Psychology, 68(1), 70–77. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.68.1.70

Simons, D. J., & Chabris, C. F. (2011). What people believe about how memory works: A representative survey of the U.S. population. PLoS ONE, 6(8), e22757. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0022757