Extrasensory Perception: Science or Superstition?

In Spring 2025, students in Dr. Emily Stark’s Introduction to Psychological Science course completed a research project where they identified a misconception related to psychology, conducted both background research and an empirical project measuring belief in that misconception, and summarized their findings in a short blog post paper. The goal was to build student research skills as well as showcase the importance of thinking critically about information encountered in the media or in popular culture. This post is one of the papers submitted for that course. For more information on this project, just use the contact page to contact Dr. Stark.

By Aidan Zender

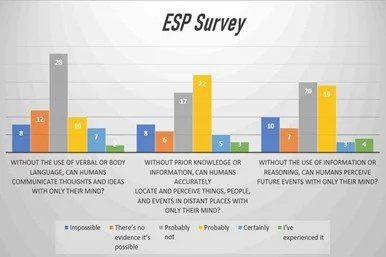

From ancient legends like the Oracle of Delphi to comic book super heroes like Spider-Man, the concept of extrasensory perception has fascinated humans for thousands of years. But what is extrasensory perception, or ESP for short? ESP is the paranormal ability for humans to receive and transfer information without the use of your physical senses. The most well known examples of ESP are telepathy, clairvoyance, and precognition. Telepathy is the ability to communicate information and ideas with others only using the mind. Clairvoyance is the ability to locate and perceive distant places, events, and people. Precognition is a subcategory of clairvoyance, and is the ability to perceive future events without the use of information or reasoning. In an article from Gallup (2005) Americans were polled on their belief in paranormal phenomena, and they found 31% of Americans believe in telepathy, 26% believe in clairvoyance/precognition, and 41% believe in ESP generally. Although the polling is twenty years old it shows that a large amount of Americans believe in ESP. We conducted a survey using Qualtrics to evaluate people's attitudes and beliefs around ESP. The rate of responses varied, but the rate of 'affirmative' responses (probably, certainly, and I've experienced it) were sizable. 28% responded affirmatively for telepathy, 49% for clairvoyance, and 41% for precognition. Now that we've illustrated people's beliefs and attitudes towards ESP, is there any empirical data backing up those beliefs?

The Ganzfeld Procedure

In an article published in the British Psychological Society, Robinson (2009) reviews the history of the 'Ganzfeld Procedure.' The Ganzfeld procedure is an experimental method testing a subject's telepathic abilities, it attempts to see if a 'sender' can relay a message to a 'receiver' through mental transmission. The experiment goes as follows: The receiver is situated in an isolated room wearing headphones playing white noise while wearing translucent ping-pong balls cut in half cover their eyes as a red light shines above them. The purpose is to put them in a state of sensory deprivation, which many parapsychologists anecdotally claim is conducive to ESP experiences. The sender is in a separate room and is shown randomly selected visual stimuli, they are tasked with transmitting the image to the receiver, while the receiver vocalizes any thoughts or images which come to mind. Upon the completion of the session, the receiver then selects one of four images, and is asked to choose which one they think the sender was trying to transmit. A skeptic would assume their choice would be random and the rate of alignment between the sender's transmission and the receiver's image would average out at around 25%, but early Ganzfield experiments yielded striking results. A meta analysis of 28 studies between 1974 and 1981 (Honorton, 1985) found a 35% accuracy rate, a massive gap considering the amount of data that was analyzed. This may seem to confirm the ESP hypothesis, but now there are many concerns that the methodology was flawed. In retrospect the poor randomization of images and possible sensory leakage has rendered the findings indeterminate under scrutiny.

The Auto-Ganzfeld Procedure

Based on the flaws of the Ganzfeld procedure, a more reliable method for testing telepathy was developed known as the Auto-Ganzfeld procedure. The Auto-Ganzfeld procedure's methodology differs in its more rigorous standards which attempt to weed out any flaws in the original; namely the randomization and selection of visual stimuli were computerized to prevent any unintended interference. Even with the more diligent approach, the Auto-Ganzfeld procedure once again produced noticeable results. In an article published in the Psychology Bulletin (Bern & Honorton, 1994) analysis of 354 Auto-Ganzfeld sessions in 11 separate studies showed a 32% average rate of alignment for the images sent between senders and receivers. This extraordinary data has subjected these studies to heavy amounts of criticism over time, and with more experiments and data to analyze, the findings are less dramatic. In response to Honorton and Bern's analysis, Milton and Wiseman (1999) performed a meta-analysis of 30 Auto-Ganzfeld studies in 1999, and across all published Auto-Ganzfeld studies they found no significant disparity in data between the results and the expected outcome.

Daryl Bem: Pioneer or Sophist?

In 2011, social psychologist Daryl Bern of Cornell University published an article in the Journal of Personality and Psychology (Bern, 2011) which would cause a wave of controversy in the science community. Bern was previously mentioned for his work with Honorton on the Auto-Ganzfield procedure. In the article Bern reports on nine different experiments, eight of which he claims show evidence for the existence of precognition. Bern specifically highlights two aspects of precognition he hypothesizes could be evolutionarily advantageous; the anticipation of desirable erotic stimuli, and the anticipation of undesirable negative stimuli. To see the validity of his claims, let's first review how these experiments were conducted.

The participants were presented with two images shrouded by curtains on a computer program, they were told behind the curtains one had an image, the other did not, and to select which curtain they felt had an image behind it. From the participants' perspective these experiments tested for clairvoyance, but what they didn't know was both curtains had an image, only one had a sexually explicit image, and the other was neutral. The test was to see if the participants were more inclined to unconsciously choose the desirable erotic image, displaying a form of unconscious precognition. Participants would go through 36 trials, selecting between the two unknown images. The ESP hypothesis was that participants would select arousing images over the threshold of random chance, 50%. There were 100 sessions in total and the results were significant. Participants selected the erotic images on average 53.1% of the time, seemingly confirming the ESP hypothesis. Another experiment in Bern's article, the retroactive facilitation of recall, produced some stunning results. For this experiment, participants were seated at a computer and presented with a series of 48 words, each staying on the screen for 3 seconds at a time. All words belonged to one of four categories; foods, animal occupations, and clothes. After the series of words were presented they were given a test to see if they could recall the words in the order they were presented. Once the test was finished they were then asked to review the 48 words and were informed all words belonged to four categories. For the review they were tasked to categorize 24 of the words on the test into the four categories above, and the other 24 were no-practice control words. The goal was to see if reciting and typing out the words during the review would retroactively influence their ability to recall them after the test, signaling a retro-causal link in the information obtained in the future affecting the past. Once again, the results seemed to align with the ESP hypothesis; the words recited after the test seemed to positively affect the participants ability to recall them after the test by a 2.27% margin.

The results of these experiments appear to be a groundbreaking discovery, and if true have massive implications on our current understanding of physics and biology. Due to these extraordinary findings, the experiments needed to be replicated to see if there was any truth behind the data they produced. Three separate attempts to replicate the retroactive facilitation of recall experiment (Ritchie, Wiseman, & French, 2012) all showed there was no statistically significant difference between the practiced words and the ability to recall those words after the test. But, replication studies can only show that scientists were unable to replicate the original findings and cannot explain how Bern arrived at such statistically significant results. An article in Slate (Enger, 2017) combed through Bern's past and provided an interview which may shed some light on these seemingly impossible results. These are full quotes to give an idea of his approach to the scientific method:

"I'm all for rigor, but I prefer other people do it. I see its importance-it's fun for some people-but I don't have the patience for it. If you looked at all my past experiments, they were always rhetorical devices. I gathered data to show how my point would be made. I used data as a point of persuasion, and I never really worried about, 'Will this replicate or will this not?"

Another quote from Bern referring to his process of data collection with Enger's commentary:

"I would start one [experiment], and if it just wasn't going anywhere, I would abandon it and restart it with changes," Bern told me recently. Some of these changes were reported in the article; others weren't. "I didn't keep very close track of which ones I had discarded and which ones I hadn't," he said. Given that the studies spanned a decade, Bern can't remember all the details of the early work. "I was probably very sloppy at the beginning."

The lack of replicable data and clear scientific malfeasance caused the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology to retract the article in 2018, returning the topic of precognition to the realm of speculation with no empirical basis, and leaving Bern with a controversial reputation.

The Future for ESP

The heated debate in the scientific community on the existence of ESP still continues, with arguments and objections between skeptics and researchers. This debate isn't a matter of faith (belief or disbelief) but between the data obtained and the methods used, showing the inherent difficulty of finding empirical data on paranormal phenomena. In an article published in the Scientific American, Shermer (2003) posits that the traces of unsubstantial data we do have do not meet the two pillars of proper scientific rigor; data and theory. Without clearly replicable data and a sound framework to structure it into something meaningful all inquiries into ESP are rendered speculative until substantial evidence is found. Shermer's point is correct, but parapsychologists also correctly point out that scientific inquiry into ESP is underfunded compared to other fields of study, which could be the reason there has not yet been a breakthrough in the field which could establish systems and theories based on sound data. With the lack of continuous scientific inquiry, and the lack of sound data to draw theories upon, the scientific reality of ESP remains a deadlock.

References

Bern, D., & Honorton, C. (1994). Does psi exist? Replicable evidence for an anomalous process of information transfer. Psychological Bulletin. 115 (1), 4-18. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0033-2909.115.1.4

Bem, D.J. (2011). Feeling the future: Experimental evidence for anomalous retroactive influences on cognition and affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100(3), 407-425. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/a0021524

Engber, D. (2017, June 7). Daryl Bem proved ESP is real. Which means science is broken. Slate. https://slate.com/health-and-science/2017/06/daryl-bem-proved-esp-is-real-showed-science-is-broken.html

Gallup Organization. (2005). Three in four Americans believe in the paranormal. Gallup. https://news.gallup.com/poll/16915/three-four-americans-believe-paranormal.aspx?

Honorton, C. (1985). Meta-analysis of psi ganzfeld research: A response to Hyman. Journal of Parapsychology, 49(1), 51-91. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1986-05165-001

Milton, J., & Wiseman, R. (1999). Does psi exist? Lack of replication of an anomalous process of information transfer. Psychological Bulletin, 125(4), 387-391. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0033-2909.125.4.387

Ritchie, S. J., Wiseman, R., & French, C. C. (2012). Failing the future: Three unsuccessful attempts to replicate Bern's 'retroactive facilitation of recall' effect. PLOS ONE. 7 (3), e33423. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0033423

Robinson, E. (2009). Extra-sensory perception: A controversial debate. The Psychologist, 22(7), 590-592. https://www.proquest.com/docview/622053027?

Shermer, M. (2003). Psychic drift. Why most scientists do not believe in ESP and psi phenomena. Scientific American. 288 (1), 31. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/psychic-drift/